Context

The agency was born from a conversation about what it could become.

Riff's founding architecture firm — LSW Architects — had something most agencies spend years trying to build: genuine trust with Pacific Northwest businesses. Business owners who'd collaborated with them on buildings were already in a relationship, not a sales cycle. What the firm didn't have was any creative capability to serve those relationships beyond architecture.

The founder had a rough concept — an "incubator" of sorts, a way to extend the firm's value beyond architecture into adjacent creative services. Sitting across from him in that interview, what I heard was a classic full-service agency opportunity inside a promising but undefined idea. The client relationships were real. The demand was real. The question was whether someone could see it clearly enough to build it intentionally.

I was hired as a graphic designer. I walked in knowing what this needed to be — and spent the next four years making the case for it and building it, one decision at a time.

The vision for Riff as a real creative agency — not a passion-project incubator — was the thing I brought on day one. Everything else was the work of building it.

Building the Team

Building toward a full-service studio, one strategic hire at a time

Every hire at Riff was made with a specific capability gap in mind. The goal from day one was a full-service creative studio — design, technology, production, and client services all under one roof — and the team was built deliberately toward that vision.

Founding — Design, Photo & Video

Three services from day one

We launched with immediate creative range: graphic design, photography, and video. The architecture firm had an architectural photographer on staff who became my first creative partner at Riff — combining her photography skills with my design and visual storytelling background gave us three core services to build from before the broader team was in place, and meant we could show up to early clients as a real studio, not a work in progress.

Early Growth — Technology

Bringing in a Technical Director to pair with creative leadership

Web and product design were core to the agency vision, which meant we needed engineering capability in-house rather than outsourced. Recruiting a Technical Director to own the technology side was the move that made Riff structurally viable as a full-service studio — with creative and technical leadership running in parallel from early on.

Scaling — Creative & Engineering

Building out both sides of the studio

As client work grew in scope and variety, we expanded the team to match — designers, a video producer, social media content creator, and web & software engineers on staff and contract. Creative and engineering scaled in parallel, with our Technical Director building the engineering bench while I built the creative one.

At Scale — Full Studio

15+ people, fully cross-functional

At full scale, Riff had a complete design team, engineering team, production team, and client services function — plus project managers and team coaches running corporate workshop services. The studio was operationally independent and capable of taking on complex, multi-discipline engagements from pitch to delivery.

From the people who were there

"Mack's effortless creativity and contagious positive outlook makes work more like play, and the outcomes more meaningful."

Casey Wyckoff

Founder & Owner, Riff Creative + LSW Architects

The person who brought me in as employee #1

"During my early and formative years as a designer, he led with thought, intention, and most importantly, kindness. He's an insanely talented creative with a knack for bringing people and ideas together."

Elena Anunciado

Senior Art Director, adam&eveDDB

Designer hired at Riff

"Mack is a designer and creative director who holds high standards and always raises the bar for the work at hand. A creative professional who can move through challenges and ambiguity with curiosity and ease."

Corinna Scott

Senior Design Strategist, The Program

Designer hired at Riff

"Mack leveraged his role as my Creative Director to nurture my own creative ideas, carefully drawing out my strengths and abilities."

Nate Shipps

Video Production Lead, Riff Creative

Hired and developed at Riff

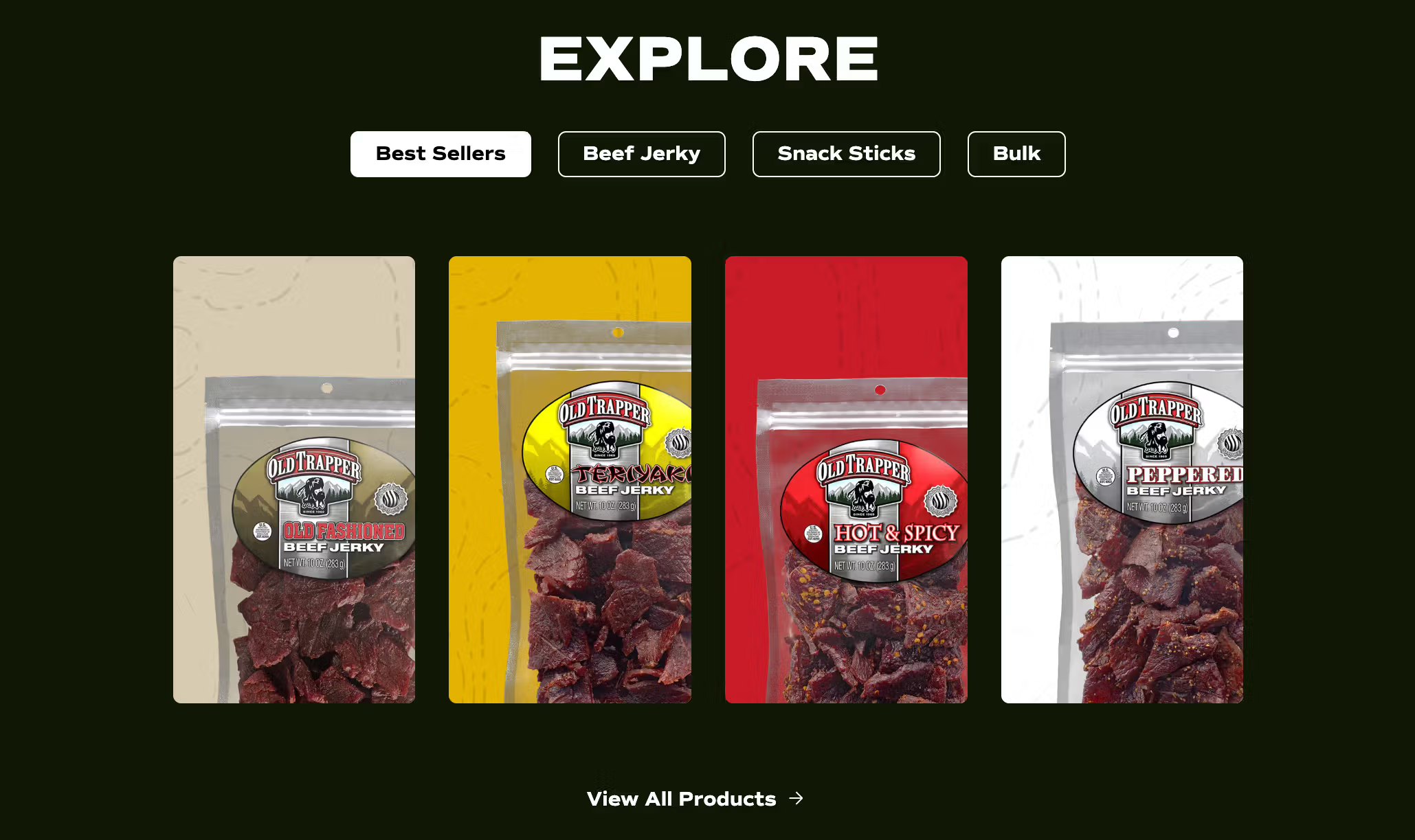

"Mack is a leader who brings teams together, guiding both creative and strategic decisions to drive meaningful impact. He blends strategic thinking with exceptional design instincts."

Robert Leary

Chief Marketing Officer, Old Trapper Beef Jerky

Riff client

Building the Process

You can't scale what isn't written down

One of the most important things I learned early at Riff: creative quality doesn't scale through talent alone. It scales through systems. As the team grew, I built the operational infrastructure that let us deliver consistent, high-quality work without everything running through me.

01

Creative brief & intake

Built a structured brief process that forced the right conversations before any creative work started — eliminating the most common source of revisions and client frustration.

02

Project management system

Stood up the studio's project management workflow — how work moved from brief to concept to production to delivery, with clear handoffs and accountability at each stage.

03

Design review process

Established a structured internal review before anything went to a client. This raised the floor on quality across the whole team and created a culture of constructive feedback.

04

Pricing & scoping frameworks

Built the models we used to price and scope new work — ensuring projects were profitable and that scope creep was caught and addressed before it became a problem.

05

Hiring rubric

Created the criteria and interview process we used to evaluate candidates — ensuring we were hiring for the right combination of craft, culture fit, and growth potential.

06

Riff's own brand standards

Built Riff's visual identity and brand standards — establishing who we were as a studio and giving the team a shared creative language to work from.

The brief process, the review cadence, the scoping models — these weren't constraints on creativity. They were the conditions that made consistent creativity possible. Structure isn't the opposite of creative freedom. It's what you build so creative freedom doesn't eat itself.

The Work

Creative direction across branding, web, and product

As Creative Director I set the direction and quality bar across every client engagement. Riff's services spanned branding, web design, product design, photography, video, motion graphics, social media content, and campaign work — and my job was to make sure every discipline, every deliverable, held the same standard.

Brand Identity

Print & Collateral

Campaign

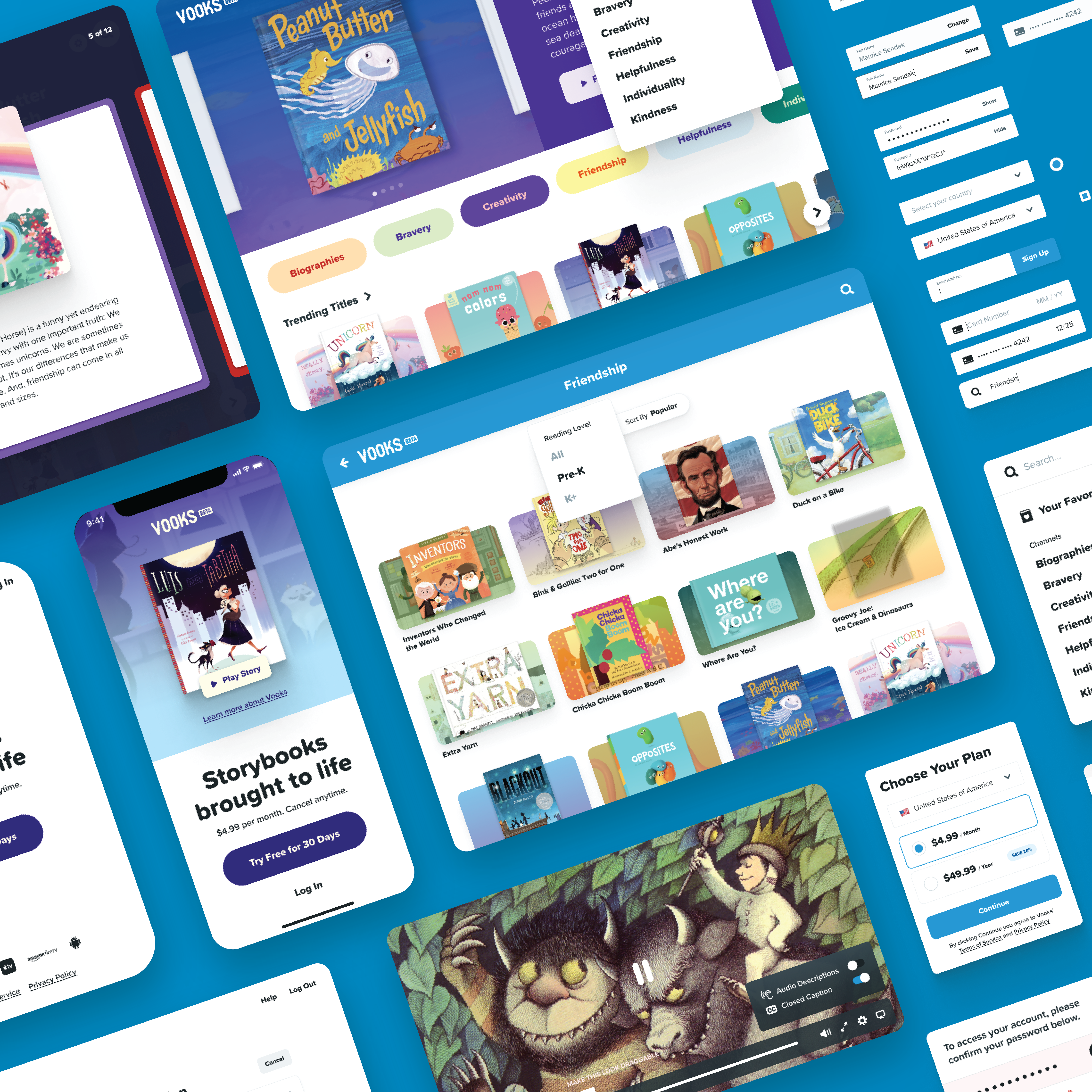

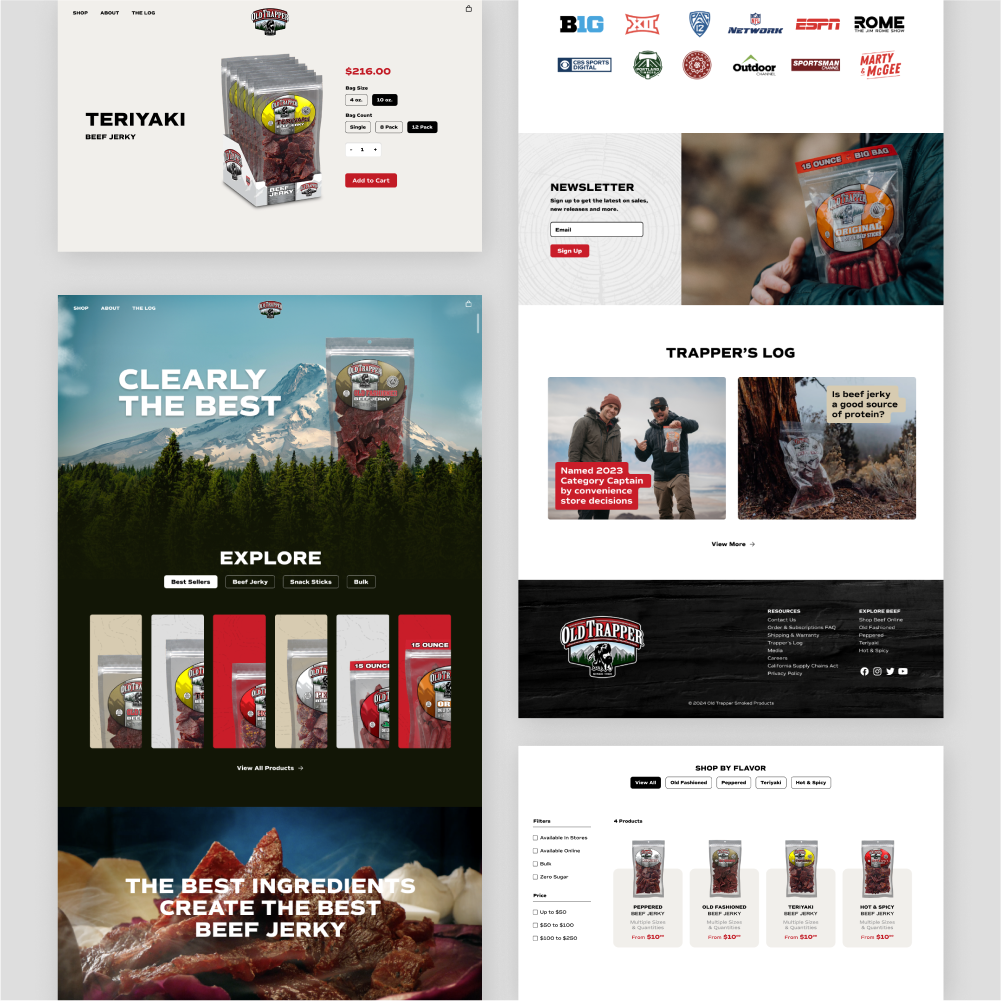

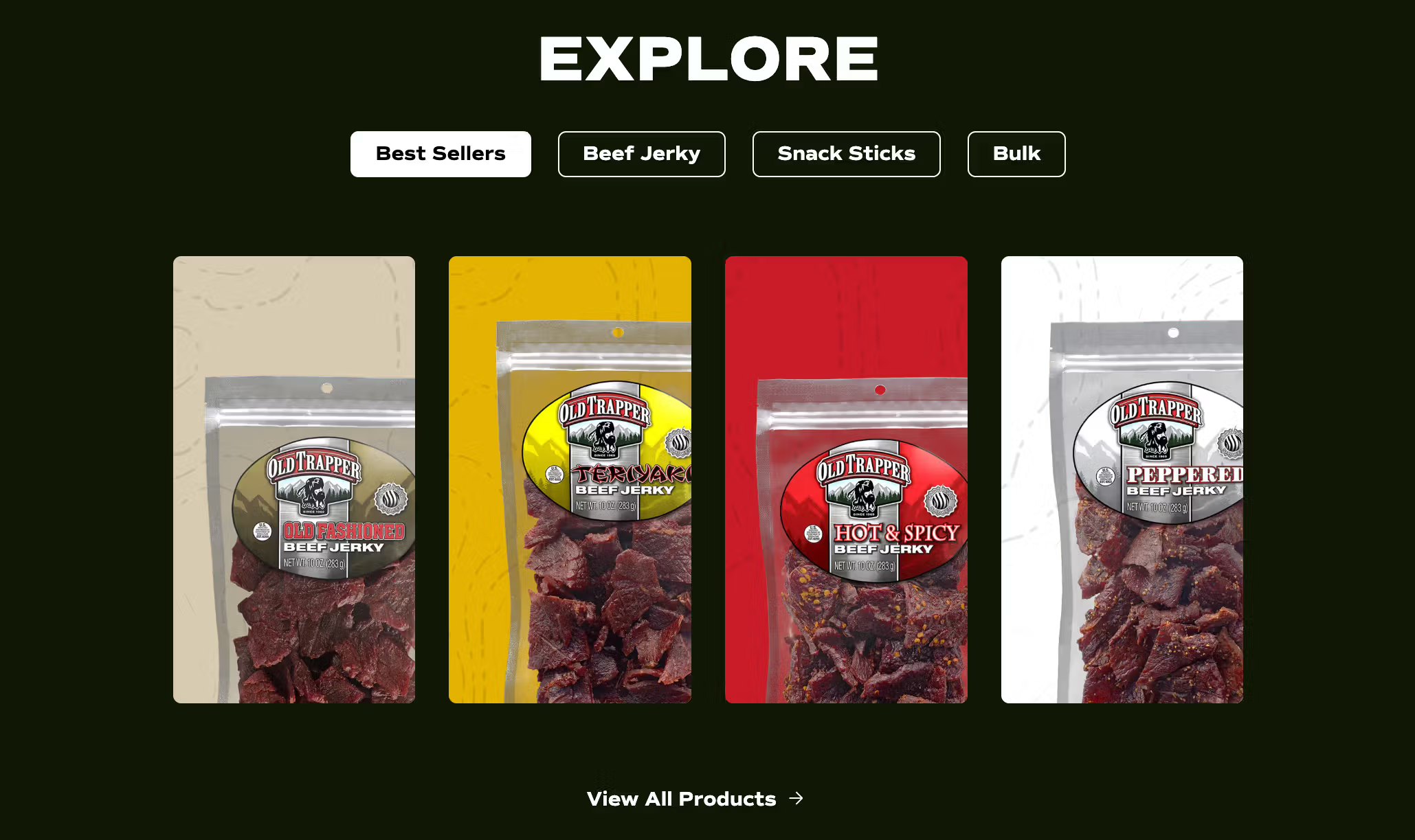

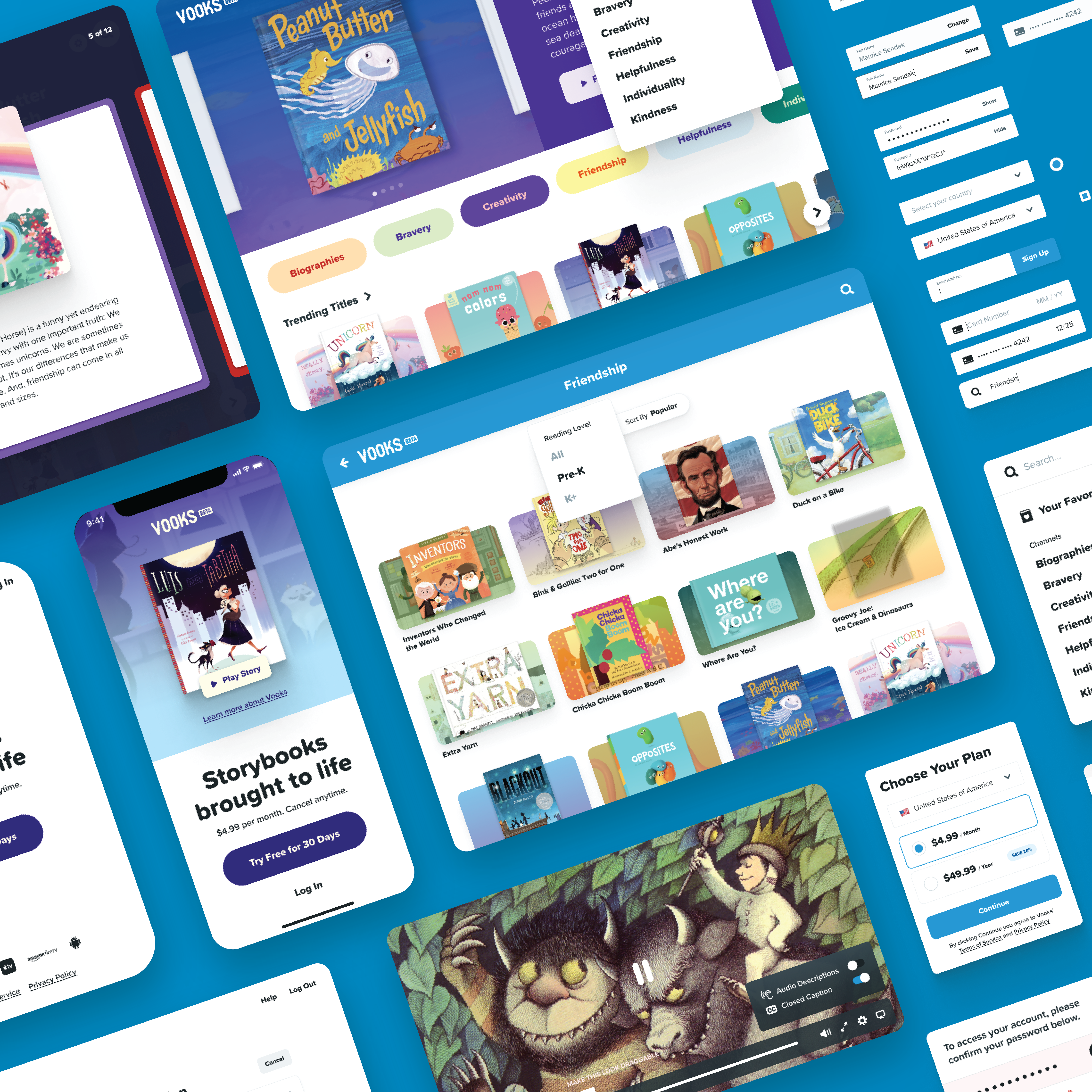

Product Design

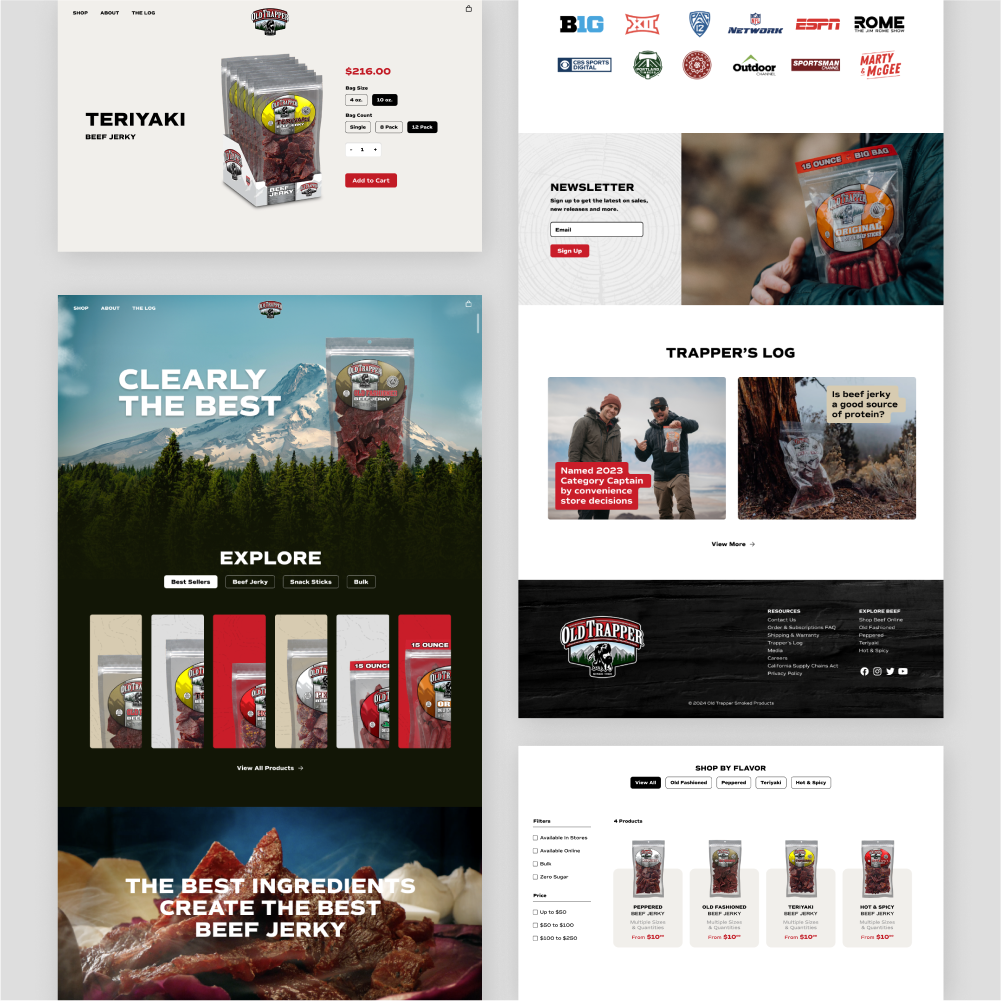

Web Design

Motion / Video

Product Design

Web Design

Brand Identity

Photography

Brand Identity

Studio & Culture

Web Design

Selected client work from Riff Creative, 2019–2023.

Pitching and winning new business

Beyond leading the creative work, I was in the room for client pitches — presenting concepts, defending creative decisions, and building the trust that turned prospects into long-term clients. This experience shaped how I think about design communication: the ability to articulate why something is right, not just show that it looks good, is one of the most undervalued skills a creative leader can have.

What I Learned

What building a studio taught me about leading design

The Riff years were the most formative of my career — not because of any single project, but because of the accumulated experience of building something from nothing alongside people I hired, developed, and ultimately trusted to carry the work forward without me.

Hiring is the highest-leverage design decision you make. The people you bring in determine the culture, the quality bar, and the ceiling of what's possible. I got better at this over time — and I still think about it as a craft.

Process is creative infrastructure, not bureaucracy. The brief process, the review cadence, the scoping models — these weren't constraints on creativity. They were the conditions that made consistent creativity possible at scale.

The best creative leaders make themselves unnecessary. My goal was always to build a team and system where the quality of the work didn't depend on me being in every room. By the time I left, it didn't.

Design and business are the same conversation. Owning client relationships and being in pitches taught me that great design work lives or dies on the strength of the case you make for it. Craft and communication are inseparable.